Twenty-three educators, sustainability coordinators, and administrators from PAISBOA member schools gathered at The School in Rose Valley (SRV) for the PAISBOA Sustainability meeting, co-organized by PAISBOA and Boyer Sudduth Environmental Consultants (BSEC) on October 9th, 2025. This event provided a space for participants to share ideas, highlight campus initiatives, and strengthen connections around environmental sustainability.

Growing a Sustainable Culture in Our Schools: AIS Hosts the PAISBOA Sustainability Meeting

On Wednesday April 30th, more than 30 educators, sustainability coordinators, and facilities staff from PAISBOA member schools came together for the group’s semiannual sustainability meeting, co-organized by PAISBOA and Boyer Sudduth Environmental Consultants (BSEC). This spring’s gathering was hosted by The Agnes Irwin School (AIS) and offered a space to share ideas, explore campus initiatives, and build connections around school sustainability.

The Hidden Cost of Food Waste and How You Can Address it Locally

Every day, the average American produces 4.9 pounds of trash — a staggering amount that contributes to overflowing landfills and environmental harm. A significant portion of this waste comes from food. In fact, 30-40% of the U.S. food supply is wasted, the equivalent of bringing home three grocery bags and tossing one straight into the trash.

By making small changes, we can reduce waste, save money and help protect the planet. Let's make every day Earth Day, starting with what's on our plates.

Sorting It Out: Abington Friends’ Waste Audit in Action

Did you know the average American produces nearly 5 pounds of waste per day (EPA, 2024)? Schools generate a significant amount of waste, from lunch trays to classroom materials, much of which could be diverted from landfills.

To better understand their impact, 7th Grade students at Abington Friends School conducted a waste audit, sorting and analyzing a school day’s worth of trash.

Brewing Sustainability: One Café’s Eco-Friendly Journey

At EB Coffee & Pub (EB), owner Justin Nichols and his team envision a vibrant community hub where every cup of coffee tells a story of quality, sustainability, and connection. From reducing waste with recyclable and reusable materials, to prioritizing local suppliers, and fostering partnerships with local community groups, the goal is to make sustainability an integral part of daily operations. EB Coffee & Pub demonstrates how small, local businesses can contribute to a sustainable future.

Food Recovery: How Boston College Prioritized Sustainability During COVID-19

After millions of students were out of the classrooms, and academic institutions were forced to transition online due to COVID 19, academic dining facilities were left with unforeseen revenue losses and potentially large sums of food waste. Colleges specifically were left with almost empty dining halls and overflowing kitchens. While colleges and universities, like Boston College, were able to allot stocked meals for students and faculty still on-campus, dining facilities were forced to find creative ways to incorporate food recovery in their operations.

Top Tips For Getting started with Sustainable Food Services

Turning Food Waste into Food Recovery at School

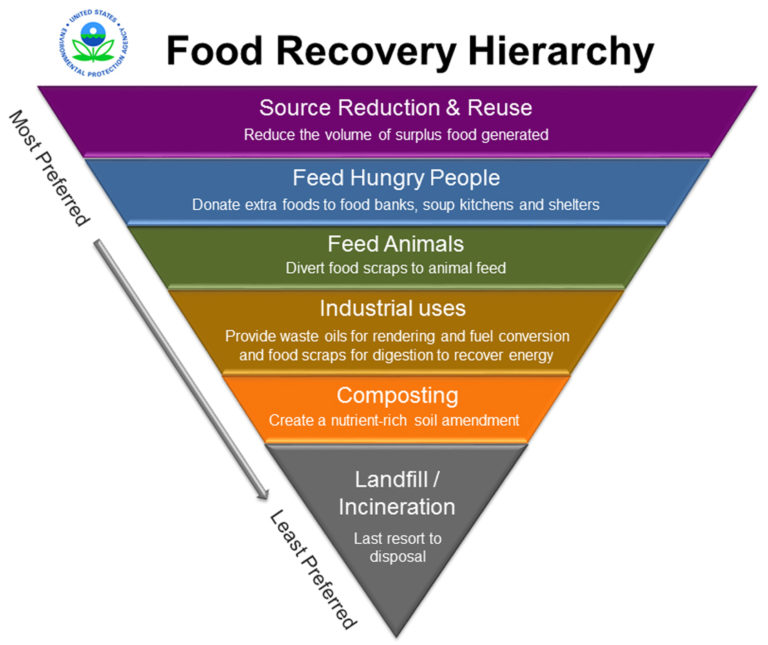

EPA’s Food Recovery Hierarchy

https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/food-recovery-hierarchy

In the United States, food waste is a growing problem. Currently, about 40 percent of food is thrown away without any effort to divert it from the landfill. By weight, 63 million tons of food are wasted in the US alone every year. Not only is this behavior a gross misuse of food, but growing, processing, and transporting food is a major draw on resources. Food waste alone consumes 21 percent of all freshwater, 21 percent of landfill volume, and 19 percent of cropland (ReFED, 2018). The energy the US wastes on discarded food in a year is about twice as much energy Switzerland uses in a year (Webber, 2010) . Meanwhile, one in seven Americans are food insecure, meaning they lack reliable access to affordable, nutritious food (USDA, 2017). Due to the scale of this problem, the EPA has created a Food Recovery Hierarchy, a comprehensive graphic that outlines preferred food recovery techniques, with feeding hungry people and source reduction being the best practices.

Of the $218 billion worth of food wasted every year in the US, $1.2 billion is from school lunches (Bloom, 2016). In a study of four Boston schools, 26.1% of the food budget was thrown away by middle school students annually, not including the extra food that was never served (Cohen, 2013). While school lunch waste makes up a fraction of the wasted food in the US, it is an imperative problem to address. The K-12 educational system is an incredibly important piece of the American society, for it shapes the minds of its young generations. What these students learn in school can develop their passions, their habits, and their understanding of the world-- including the problems it faces. Allowing such waste in the school system teaches children that food is garbage, disposable and of little value. The USDA has introduced the Food Waste Challenge, a food waste reduction challenge for schools to participate in. Some schools have taken major steps towards reducing food waste and making students apart of the process so they can continue the legacy.

How You Can Have a Role in Change

Addressing food waste is a new and growing issue, but school administration can often be too busy to tackle the problem. So, it is often up to inspired community members to spark the change they would like to see. Wellesley, Massachusetts has an exemplary food waste reduction system, with programs including food share tables in elementary schools and a food donation system. These food recovery efforts began with a few concerned parents, teachers, and a motivated Food Service Director. From that grassroots beginning, food recovery projects have sprouted up in all K-12 schools in the Wellesley school district.

In the elementary schools, one parent took a special interest in food waste and was able to spark interest amongst fellow parents. With the help of custodians and the Bates Elementary School principal, they began looking into how to reduce consumer waste with their young students. To start, an experiment was conducted to discover what exactly was being thrown away by examining their waste. After this initial waste audit, Matt Delaney, the school’s Food Service Director from Whitsons Culinary Group, jumped on board. Three important steps were then taken:

Food services cut back on the food that was not being sold.

Kitchen staff went through a training process on how to package food eligible for donation.

Food that was not being sold or even put out was packaged up and taken by volunteers to food pantries.

Today, excess prepared food is frozen and then picked up by Food for Free, a food rescue organization, every two weeks and taken to nonprofits in need of food. Since then, Mr. Delaney has made great efforts to tailor meals and portions so that food waste is minimized. Future goals include expanding the school’s reusable “green” food container supply and introducing food waste composting to all cafeterias.

Green Containers used by Wellesley Public Schools. Source: Matt Delaney, Whitsons Culinary Group

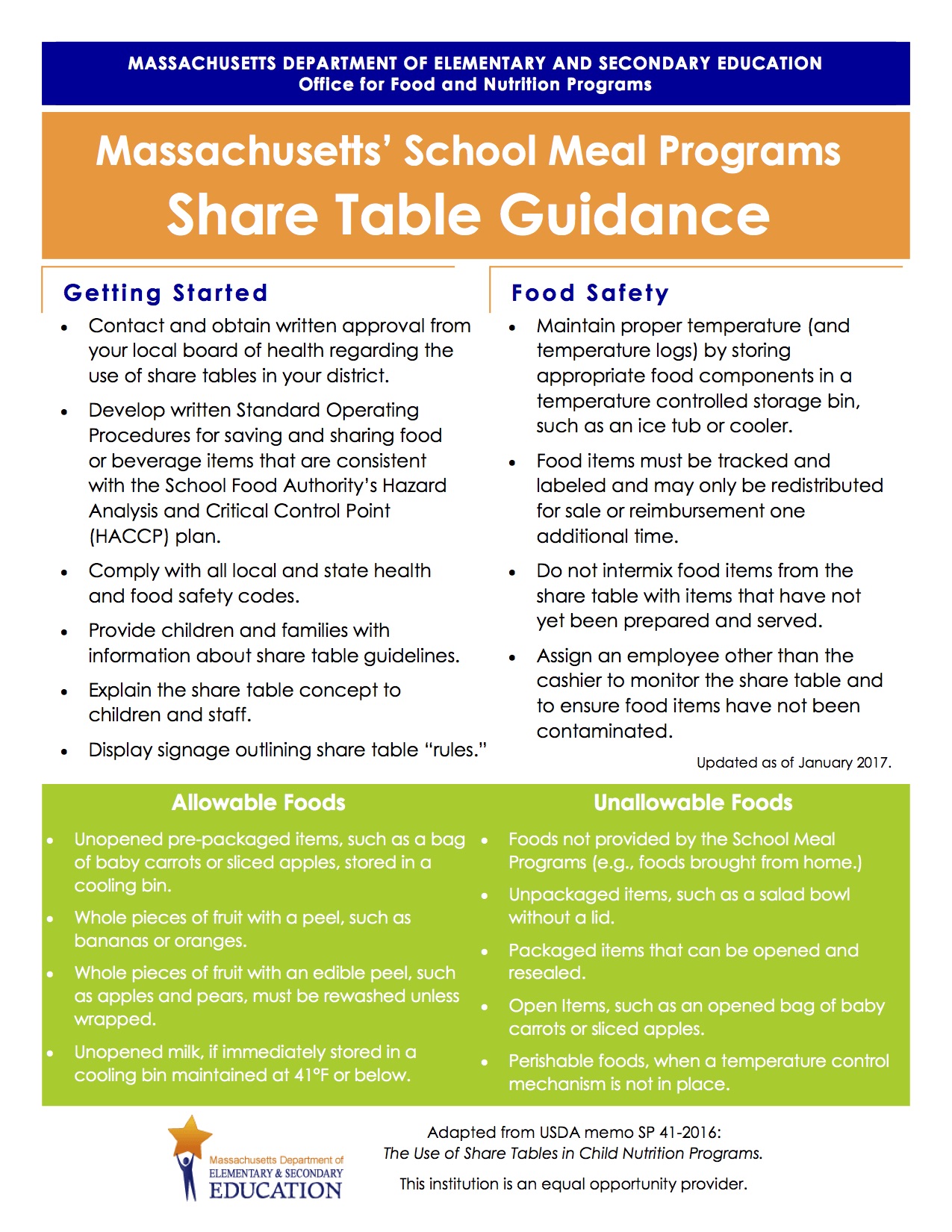

After learning that the school was throwing away edible food in the initial student led waste audit, Bates Elementary School began a “share table.” Share tables (often found in elementary schools) are areas where students can leave their unopened food so that it can be redistributed. At Bates, students leave their unopened food on a specific table after lunch so it can be redirected to students in the after school program, teachers, and town departments such as Public Works. The program has been expanded to a few other Wellesley elementary schools.

In Wellesley elementary schools, parents and the Food Service Director played key roles in inspiring and implementing the food rescue program. A hope for the future in middle and high schools is that students may be inspired to address food waste and go beyond food donations and share tables. For example, students can examine why it is important to conserve food and understand the causes of the food waste challenge in the United States. In 2015, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency set a goal of reducing food waste by half by 2030 (EPA, 2015). Consumer education will be a big part of reaching this goal. At schools, students can learn strategies for prevention, recovery and recycling of food waste. From “right sizing” portions to properly disposing of plate waste or “leftovers,” lessons about reducing and managing food waste. While curriculum is often slow to change, teachers who want to teach about food waste can work with motivated students to take the initiative to educate themselves and their peers. The links below offer some helpful suggestions for getting started.

In colleges, students often make this push. An organization called the Post Landfill Action Network (PLAN) provides resources to college students who are seeking guidance in changing the food systems at their schools. Campus Coordinators work with individual students or environmental student groups to implement waste reduction techniques such as changing portion sizes, removing trays, implementing compost, and donating unserved food. Even these students have trouble making change in consumer behavior, possibly because older students are more prone to sticking to habits. If behavioral change can be introduced at younger ages, there’s far more potential for lasting differences in how people consume their food.

How to Start Food Sharing and Donations at Your School

Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Guide to Share Tables https://thegreenteam.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Share-Table-Guidance.pdf

Fortunately, the Federal Government protects donors of food through the Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act of 1996, which encourages donations of food and grocery products to nonprofit organizations. The Act encourages donations by stating that legally, a person shall or gleaner not be subject to civil or criminal liability arising from the nature, age, packaging, or condition of apparently wholesome food or an apparently fit grocery product that the person or gleaner donates in good faith to a nonprofit organization for ultimate distribution to needy individuals” (US Cong. 104-201). Although the federal government may encourage food donations, each state and school district has different policies as to how share tables and food donations should function, if they are allowed at all. The website Food Rescue has a history of State Policy on food waste in schools, which is important to know when attempting to start a share table of your own. Some schools donate unserved prepared food by donating it to a food rescue that will distribute it to a nonprofit serving those need. Once state and local allowance is confirmed, local board of health approval is also necessary.

Other key players to work with are the food service department, custodians, and administration. Food sharing, donating, and conservation cannot be done without the help of these departments who monitor different aspects food services. Creating collaborative relationships with these people are required to the functioning of any food rescue, share, or compost operation.

Thank you Matt Delaney of Whitsons Culinary Group, Phyllis Theermann of Sustainable Wellesley, and Adina Spertus of Post Landfill Action Network (PLAN).

Written by Meggie Devlin, Intern, Boyer Sudduth Environmental Consultants LLC.

August 7, 2018

Resources for Minimizing Food Waste at your School

Federal Guidelines on the Good Samaritan Act:

Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act of 1996

LL.M Program in Agricultural & Food Law at the University of Arkansas Legal Guide to Food Recovery Laws:

https://law.uark.edu/documents/2013/06/Legal-Guide-To-Food-Recovery.pdf

ReFED Guide to State Laws on Food Recovery

https://www.refed.com/tools/food-waste-policy-finder/

Guide to State Laws on Food Rescue in Schools

http://www.foodrescue.net/school-food-waste-policy-history.html

REFERENCES

Bloom, J. (2016). Schooling Food Waste: How Schools Can Teach Kids to Value Food. Retrieved August 7, 2018, from Food Tank website: https://foodtank.com/news/2016/11/schooling-foo d-waste-how-schools-can-teach-kids-to-value-food/

Cohen, J., Richardson, S., Austin, S., Economos, C., & Rimm, E. (2013). School lunch waste among middle school students: nutrients consumed and costs. PubMed, 44(2).

Cuellar, A., Webber, E. (2010). Wasted Food, Wasted Energy: The Embedded Energy in Food Waste in the United States. Environmental Science & Technology. 2010 44 (16), 6464-6469.

Food Security in the US: Measurement. (2017, October 4). In USDA: Economic Research Service. Retrieved August 7, 2018, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/measurement/

The Multi-Billion Dollar Food Waste Problem. (2018). Retrieved August 7, 2018, from ReFED website:https://www.refed.com/?sort=economic-value-per-ton

United States, Congress, Senate. Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act. Government Printing Office, 1996. 104th Congress, Senate Bill 104-210.

United States 2030 Food Loss and Waste Reduction Goal. (2015). In United States EPA. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/United-states-2030-food-loss-and- waste-reduction-goaf

Freight Farming on Campus

Photo: Students at Boston Latin stand outside of their Freight Farm

Stepping into the shipping container on the grounds of Boston Latin School is not what you would expect. The glow of LED lights, the cool humid temperature and the abundance of leafy greens hanging from the ceilings might surprise you, but for the students in charge of maintaining this wonder, it’s just another day.

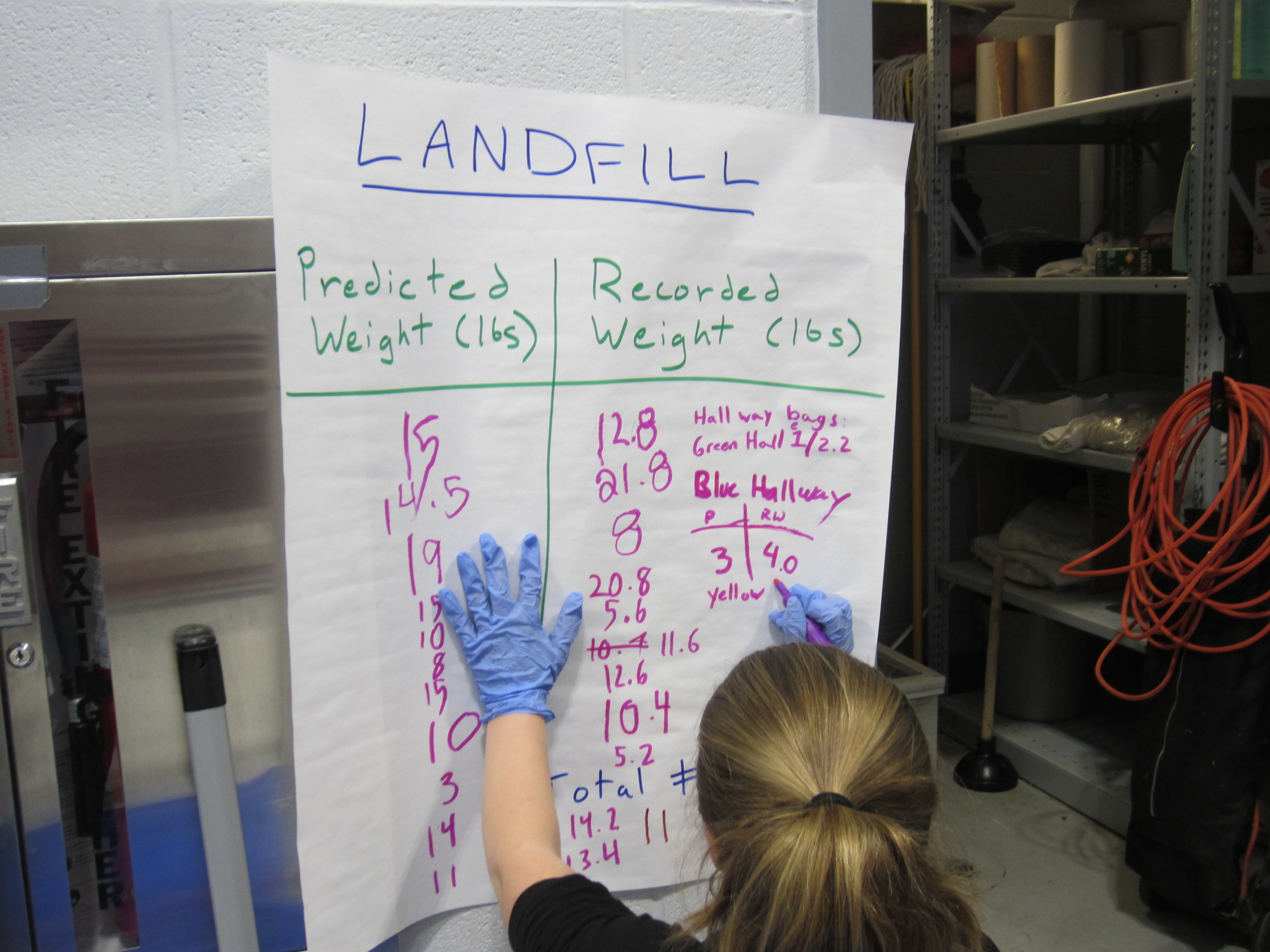

Red Clay School Goes Green: Cooke Elementary’s Waste Audit

How much waste does one elementary school produce each lunch period? This was the question that motivated William F. Cooke Elementary School’s Talented and Gifted (TAG) program students to conduct a waste audit on March 13th. Realizing that they needed to know what they were up against before they could make a change, the students of the TAG program at Cooke set out to find exactly what was in their waste

Cooke Elementary students predict how much waste they generate in the cafeteria before weighing each bag as part of their waste audit.

Teacher Christine Szegda received a grant from the Delaware Pathways to Green Schools Program. Ms. Szegda enlisted school sustainability consultants, Mary Ann Boyer and Sam York of Boyer Sudduth Environmental Consultants (BSEC) to help plan and run the audit. Together, they set the date for the first waste audit on March 13th and developed an agenda for the day.

When the day came, Ms Szegda’s TAG students, the Cooke Elementary Custodial staff, BSEC, and parent volunteers came together to make the day a success. The fact that it was chili day did not deter the TAG students, who eagerly investigated the waste in order to find the information that would let them develop an action plan for reducing waste.

What the students found was staggering: the school’s 653 students in grades K - 5 produced 153 pounds of trash and 13 pounds of recycling from just one day of cafeteria waste, and 33.4 pounds of liquid waste from emptied water and milk bottles. Using these numbers, we can estimate that in one week, the school produces 653 pounds of trash, 65 pounds of recycled materials, and 167 pounds of liquid waste. Imagine what those numbers are in a school year? But this is only a single school! As parent volunteer Lisa Call said, “Imagine how much is wasted in Delaware alone, not to mention the rest of the country.”

These numbers motivated TAG students to immediately pull together plans for how to reduce the amount of waste produced. Ms. Szegda and her students will develop an action plan for making changes to reduce waste and increase recycling. They will implement changes and conduct a second waste audit in the spring to compare their results with this first one. According to one student, "We want the cafeteria to stop using styrofoam lunch trays. They get used once and then sit in a landfill for thousands of years after!”

Students were surprised by how much food was thrown away each day. “After combing through unopened snack bags, unpeeled bananas, and half eaten lunches,” noted Ms Szegda, “they had a real ah-ha moment.” The students learned that the average American throws out 4.4 pounds of trash a day. After seeing the food waste, students began to think about more sustainable and affordable solutions. Giving students only as much food as they will eat and encouraging students to use the "share bin" would help reduce the amount of food that would end up in a landfill each day.

The students found some positive data too: almost everything that was put into the recycling was recyclable. They now know, however, just how big their task is. Over the coming weeks, Ms. Szedga and her students will look more closely at waste and help teach others about what they can do to lessen their environmental footprint. The students will review the data from the audit and develop an action plan for reducing the waste. Ms Szedga reflected, “Making effective change always takes hard work, but I’m sure the students will use their creative energy and enthusiasm to show others how to make Red Clay a greener place.”

Article submitted by Sam York, intern of Boyer Sudduth Environmental Consultants.

Friends' Central School Students Conduct Dining Hall Waste Audits, Find Surprising Results

Area Schools' Sustainability Leaders Convene at EA

On April 26th, PAISBOA held its second meeting of the year, entitled “Journey to Sustainability: The Ebbs & Flows” at Episcopal Academy (EA) in Devon, PA. EA's Director of Operations, Mark Notaro, and Win Shafer, EA’s Science Teacher and future Sustainability Coordinator, led the group of 18 members from eight area schools and sustainable business managers on a tour of EA’s Doolittle Greenhouse, community garden, chemical-free landscape, green roof, and on-site industrial sized composter.

After the tour, the group enjoyed a sustainably sourced dinner followed by a discussion facilitated by Mary Ann Boyer, co-founder and principal of Boyer Sudduth Environmental Consultants. The conversation focused around strategies that will help school representatives and business leaders be mindful and proactive when planning future meetings. Members also had the opportunity to network and share stories of their journey to sustainability.

Participant Roderick Wolfson of St. James School reflected, “I appreciated seeing the recent construction around campus and the candid presentation from Mark about what works and what doesn’t.”

The PAISBOA Sustainability Group will reconvene in the fall and continue its mission to share information among the group of engaged, insightful and highly motivated individuals to improve our schools, communities and environment. For more information about future meetings, contact Mary Ann Boyer at maboyer61@gmail.com or Al Greenough at agreenough@paisboa.org.

Written by: MaryKate O'Brien, intern at Boyer Sudduth Environmental Consultants. Published in the PAISBOA Friday Flyer on May 5th. Read the flyer HERE.

Group members explore EA's community garden and discuss maintenance strategies for sustainability initiatives on campus.

Not Your Grandmother's Gingerbread House

What do you get when you pair a future environmental engineer, an aspiring architect, some gingerbread and frosting? Not your grandmother's gingerbread house, but a sustainable one. Mary Ann Boyer met with Hill School students in the Eco Action Club to conduct a workshop on green buildings. Students incorporated lessons learned by building "green" gingerbread houses.

Compost 101: Ancillae-Assumpta Academy Does it Right

Ancillae-Assumpta Academy composts all of its dining room waste with support from their students and faculty. Ancillae-Assumpta’s green initiatives include solar panels, school gardens, outdoor education, to name a few. However, the school decided to do even more. Boyer Sudduth Environmental Consultants lead facilitated meetings with the faculty and administration to identify sustainability goals. Food Service Coordinator Sarah Wade took on composting all food waste generated by students and staff.